How Claudio Ranieri’s unique approach made Leicester City win the Premier League in 2015/16.

Introduction

5000 – 1. Those were the odds before the season for Leicester City to win the Premier League. No one could’ve ever imagined that the Foxes could pull off one of the greatest underdog stories in football’s history.

Back in the 2014/15 season on matchday 30, Leicester ranked last, and a relegation seemed inevitable. The Foxes however won 7 out of their remaining 8 games and ultimately placed 14th, which kept them in the Premier League. After that campaign though, Leicester sacked their coach Nigel Pearson and brought in the Italian Claudio Ranieri.

The Foxes had an amazing start into the 2015/16 season and ranked first after 13 games. Nevertheless, everyone still expected a dip in form and couldn’t actually imagine Leicester City lifting the trophy in the end.

However, it turned out differently. After placing first on matchday 23, the Foxes didn’t give up on their place in the table and went on to win the Premier League on matchweek 36 after Tottenham’s draw against Chelsea.

This article breaks down the tactics behind Leicester’s miracle, starting off with the players and their preferred line-up.

The team

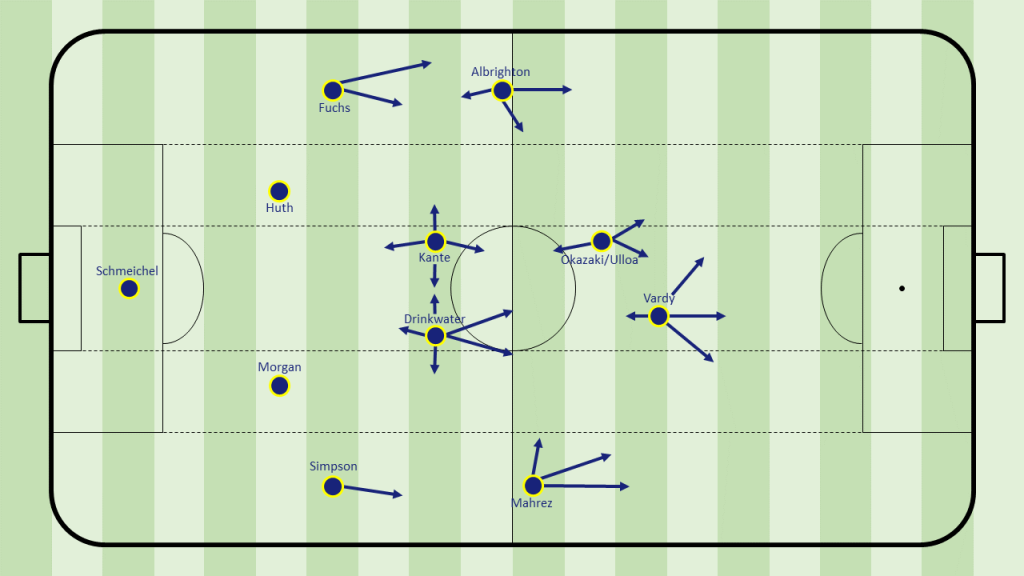

Claudio Ranieri normally set his team up in a 4-4-2 both with and without the ball. It could however be some sort of a 4-4-1-1 as well, when Okazaki was positioned deeper than Vardy. The Italian manager – also known as the “Tinkerman” – regularly changed systems and switched up players in his previous campaigns. Nevertheless, with Leicester he stuck to the 4-4-2 and mostly made use of the same players.

Kasper Schmeichel was undoubtedly the number one in goal for the Foxes and an often-underestimated factor towards their great success. The physical centre backs – Robert Huth and captain Wes Morgan – were rock solid defensively despite their lack of speed and mobility. Christian Fuchs – the left back – had a brilliant season for Leicester. The Austrian’s left foot provided a lot of chances, and his great defensive abilities were vital as well. Additionally, Fuchs’ extremely long throw-ins were a big weapon for the Foxes. Danny Simpson on the right side was strong without the ball too but more conservative than his left-sided counterpart (Fuchs) with the ball.

The double pivot of N’Golo Kante and Danny Drinkwater superbly controlled the middle of the pitch. The Frenchman especially shined with his extraordinarily high number of tackles and interceptions. In possession, Drinkwater’s forward movements and Kante’s ball-carries from time to time regularly posed a threat for the opposition.

The left winger – Marc Albrighton – continuously tracked back defensively to support his fullback. Moreover, his offensive positionings as well as his dribbles were key too. Riyad Mahrez on the other side had a standout season. The Algerian was seemingly unstoppable in 1v1s and could create chances out of nothing.

Jamie Vardy and Shinji Okazaki (or at times Leonardo Ulloa) formed the front two. The strikers’ work rate without the ball – especially from the Japanese – continuously made life difficult for the opponent. Moreover, Vardy’s various movements and runs in behind with his incredible pace were extremely threatening offensively and one of Leicester’s main chance creation methods. While Okazaki made great runs as well, he was also often seen dropping in between the lines to link up play.

A different approach

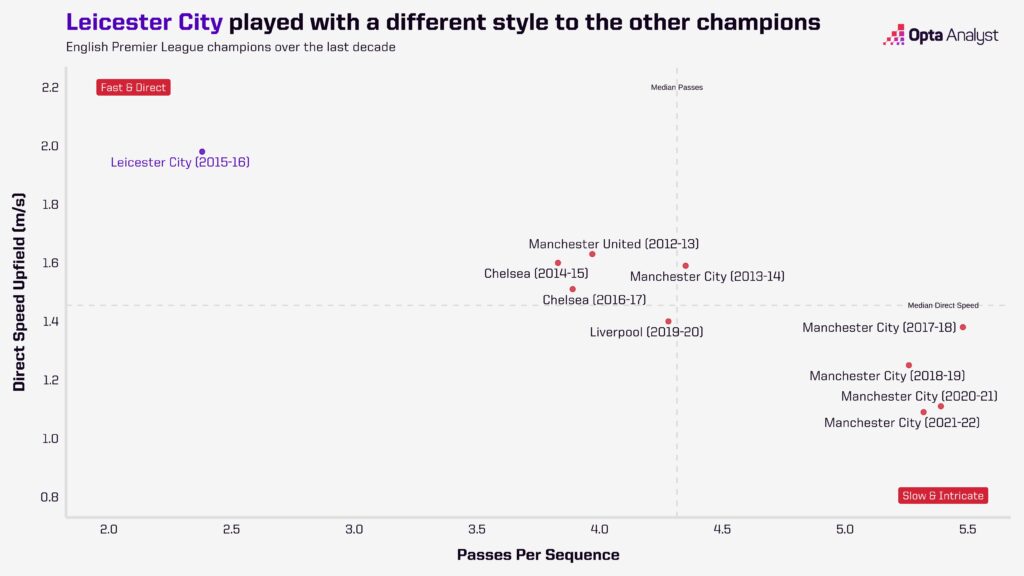

When taking a look at the recent Premier League champions, Leicester not only differs because of their history but also because of their style of play. Rather than having long spells with the ball and an approach to control the game, the Foxes let the opponent have the ball and even welcomed a transitional/chaotic game. Leicester had an average of 44.7% possession per game, which was the third lowest (place 18) in the league. Furthermore, most of their chances came from counterattacks and direct football.

The graphic below from The Analyst brilliantly shows that the Foxes were significantly different in terms of their “direct speed” and “passes per sequence” compared to the other Premier League champions over the last decade:

Constantin Eckner perfectly summarises Leicester’s style of play here in his team analysis:

“To put it simply, the idea is solely about making transitions, from the principles of counter-attacks to the shifts between single phases of pressing. This is the concept, and it leads to their using a form of counter-dynamism, which means they react on the rhythm instead of setting the pace of a match, capitalising on the opposite force that is generated by quick transition plays.” (Eckner)

Solid 4-4-2 mid to low block

As already mentioned, Leicester usually had less of the ball throughout most games (31 out of 38 Premier League games, according to FBref). Therefore, they spent a lot of time defending their goal. However, this worked pretty effectively. The Foxes only conceded 36 goals, which is the second lowest in the league (only one goal more than Tottenham and Manchester United).

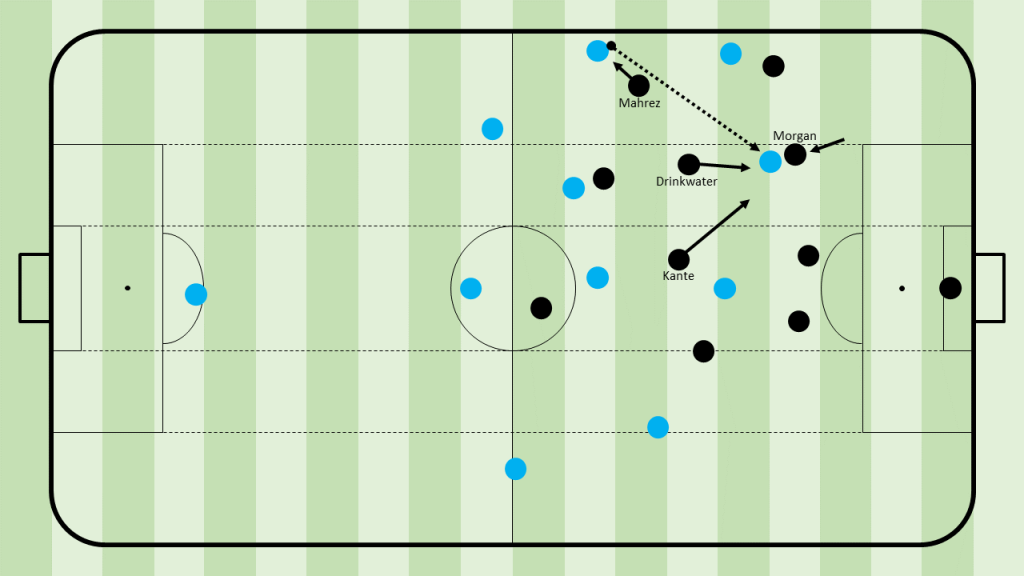

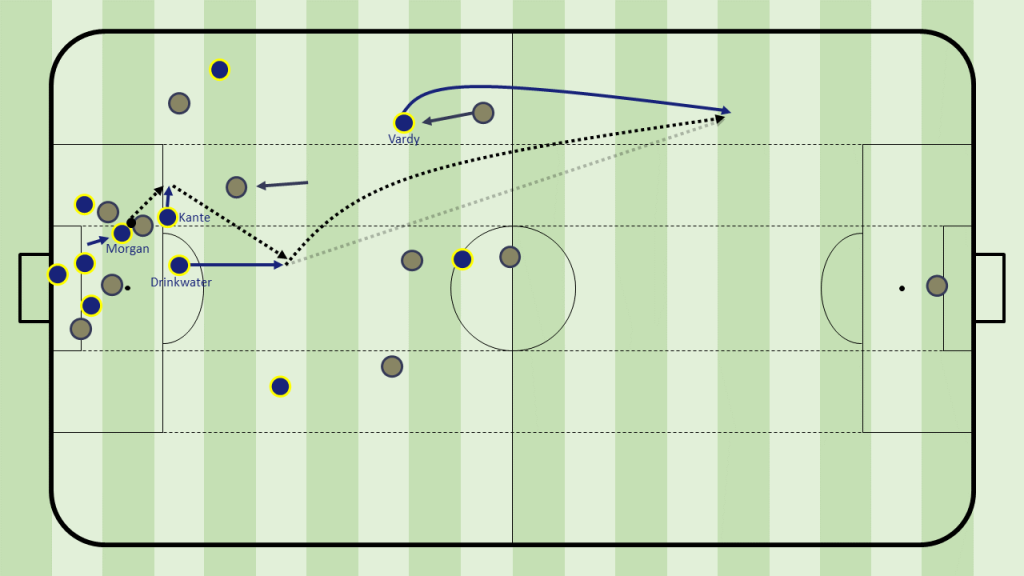

Closing the centre

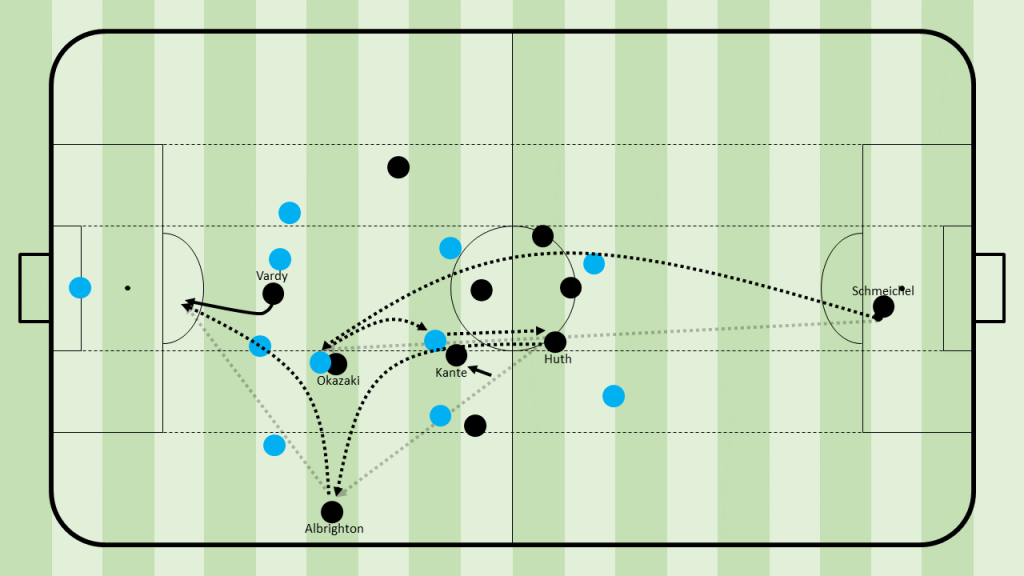

The Foxes used a compact ball-oriented 4-4-2/4-4-1-1 mid to low block with the aim to close the centre and guide the opposition towards the wide areas. Vardy and Okazaki first of all were tasked to restrict passes in the opponent’s double or single pivot by staying close to them and using their cover-shadows. The strikers rarely pressed the first line of build-up from the opposition. For instance, only after a back pass or a bad touch from a centre back. However, if they did so, then by using their cover-shadows. Moreover, if the opposition was able to access a 6, the strikers regularly pressed backwards aggressively or a 6 from Leicester could step up if needed.

Albrighton and Mahrez looked to stay narrow to ensure horizontal compactness, guide the opposition wide and suppress progression through the half-spaces. As soon as the opponent played into their fullbacks, Leicester’s wingers would engage them using a slightly curved run. The aim was to press the foot open to the field (e.g.: the right foot from the right back) and therefore ideally restrict the opposition from opening up. Furthermore, this angle in the pressing movement made it difficult for the opponent to progress diagonally through the half-space and mostly only allowed the fullback to play backwards or inside (where the Foxes were tight on the opposition).

Nevertheless, if Albrighton or Mahrez were slightly too late to press the wide defender, a vertical long line pass into his respective winger was another option. However, the receiver was then usually under high pressure from an aggressive Leicester fullback alongside the winger pressing backwards to double up (or a 6 shifted over too). In general, the Foxes’ wingers tracked back a lot to support their respective fullback and press the opposition from various angles.

The importance of the double pivot

The heart for Leicester’s defensive success was their double pivot. Kante and Drinkwater regularly shifted zonally in a ball-oriented manner. If an opponent got into the area of a 6, he would be marked temporarily (as seen in the graphic above). If the opposing player left the zone of a Leicester 6 again, Kante or Drinkwater wouldn’t follow them too far to not open any spaces in the centre/in between the lines.

Tom Payne talks about this approach of defending in his analysis on Arsenal against Leicester:

“When not tasked with covering a nearby attacker, the team will maintain their shape in their base positions and cover the space in a zonal structure. However when a forward moves within a defender’s vicinity they will flexibly orient themselves within their space to cover this player by keeping a certain distance away from them where they can apply pressure on a position level.” (Payne)

Both 6s covered a lot of ground and made a high number of tackles as well as interceptions. Kante in particular was unbelievable. The new signing from Caen registered the most tackles (175 tackles and 4,7 per game) and interceptions (156) in the league. He was outstanding at blocking passing lanes (81 passes blocked, which is again the most in the league), anticipating the next pass, and making use of his body. Additionally, after getting outplayed, Kante instantly turned around and looked to press backwards to get back into the structure and potentially win the ball again by coming from the blind-side.

This video below showcases some of his best tackles. Kante pressing backwards can be beautifully seen in the second tackle against Arsenal:

Robust centre backs and an outperforming keeper ensure defensive solidity

As stated earlier, the centre backs (Huth and Morgan) weren’t the most mobile defenders but still of huge importance for the Foxes. They dealt extremely well with long balls and crosses due to their height and physicality. Additionally, Morgan blocked the third most shots in the league (41), while Huth blocked 34 shots (8th highest).

If, although rarely, the opposition managed to access the centre, the ball-carrier was normally under huge pressure from the centre backs stepping off their lines with great timing (often alongside a 6 pressing backwards). This aggressiveness in the centre made it extremely difficult for the opposition to create anything meaningful and normally led to a ball win for the Foxes.

Schmeichel – Leicester’s goalkeeper – had a magnificent season and was somewhat of an unsung hero to ensure defensive solidity. The Foxes were expected to concede 45 goals according to understat, which means that they outperformed their xGA by 9 goals, as they only conceded 36 times. This is obviously not solely down to Schmeichel’s performance, but the Dane made a lot of outstanding saves, stopping high-quality chances, which decided games.

The Foxes’ amazing defensive performance was now extensively discussed. However, what happens after they win the ball?

Electric counterattacks and Jamie Vardy’s brilliance

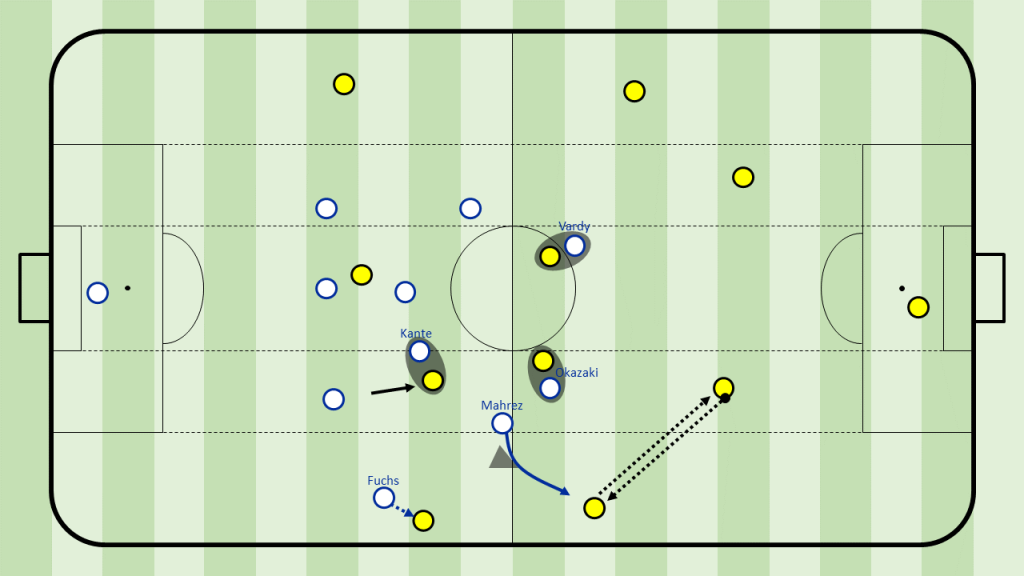

After stopping an attack from the opposition and ultimately winning the ball, Leicester looked to counterattack as quickly as possible, rather than circulating the ball. The Foxes scored 5 goals directly from counterattacks in the Premier League (the most alongside Manchester City) and created most of their chances from transitions.

Upon regaining possession, the aim was to get out of the immediate pressure (counterpressing) as fast as possible. This was ideally done by playing the ball forwards. Often, we’d see Leicester simply hitting the ball long in behind and basically hoping for the best. Nevertheless, this wasn’t always possible or not always the best option actually. Therefore, the players at times did well to combine their way out of the pressure quickly to then find a player with a forward-facing view, who could access runners attacking the depth. Dribbles into space to beat the counterpressure weren’t uncommon either. Especially Kante’s advancements with the ball, after winning it beforehand, regularly initiated counterattacks.

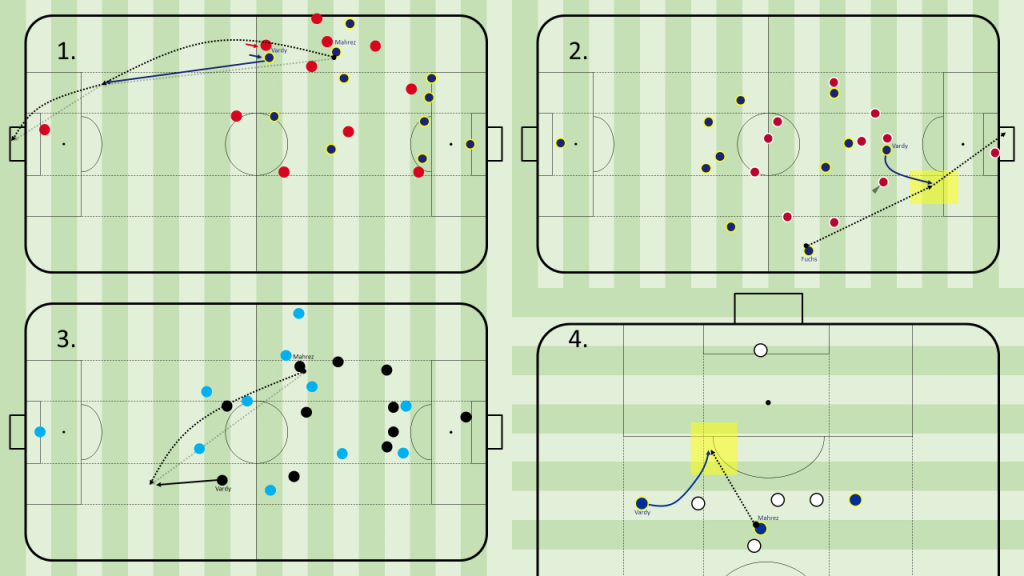

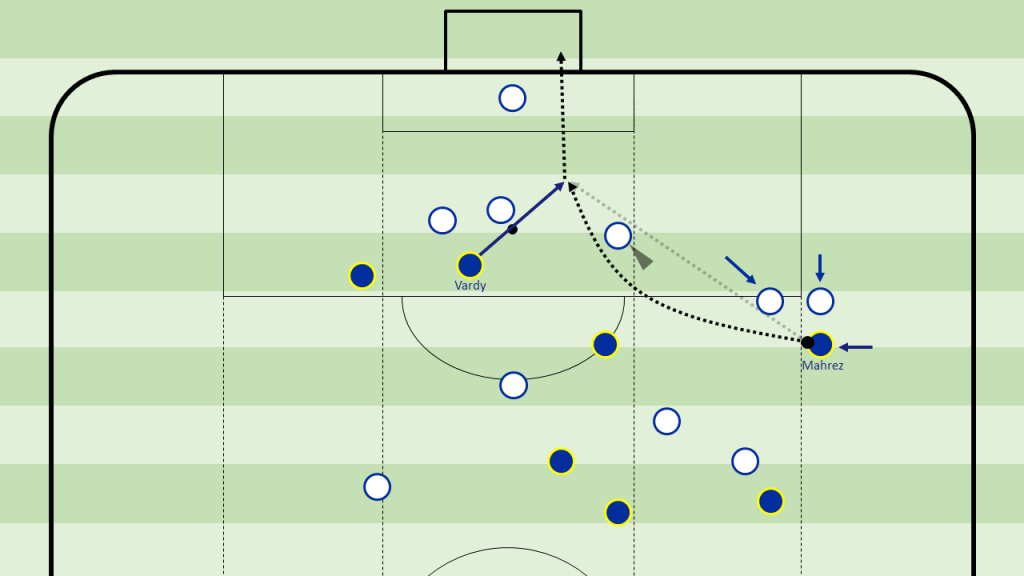

These seemingly unstoppable movements against disorganised opponents from Jamie Vardy, exploiting big gaps from the opposition, made the Foxes such a magnificent counterattacking side. The Englishman was constantly positioned on the last line, ready to dart in behind and attack the depth with his insane pace and acceleration. Vardy continuously looked to position himself on the blind-side of the defenders, making him harder to mark. This also enabled him to start his runs earlier. Moreover, the striker regularly executed bended runs to stay onside, gain momentum over his oppositions and attack gaps with a dynamical advantage. Furthermore, after Leicester regained possession, Vardy could look to create separation from his marker through clever little changes of direction. Lastly, his movements also at times acted as a decoy and could drag defenders away to open spaces somewhere else.

2: After a corner, Schmeichel instantly initiated a counterattack by throwing the ball to Fuchs. The Austrian dribbled a few metres and eventually played a perfectly weighted through ball into Vardy’s well-timed curved blind-side run. The Englishman ultimately scores.

3: After winning the ball, Mahrez instantly looks in behind for Vardy’s run. The Englishman gets past his opponent and crosses inside to Okazaki, but the Japanese couldn’t get the ball.

4: Schmeichel initiated a counterattack again by playing the ball to Mahrez. The Algerian beat an opponent in a 1v1 and eventually finds Vardy’s curved movement to stay onside in behind.

Chris Summersell brilliantly describes in his article on running in behind why Vardy’s movements are so dangerous:

“Watching Vardy operate on the shoulder of the last defensive line is an education in forward player movement. His timing, and little variations in movement is a constant threat to defenders, where his anticipation often means he is on the move sniffing out a potential opportunity before anyone else.” (Summersell)

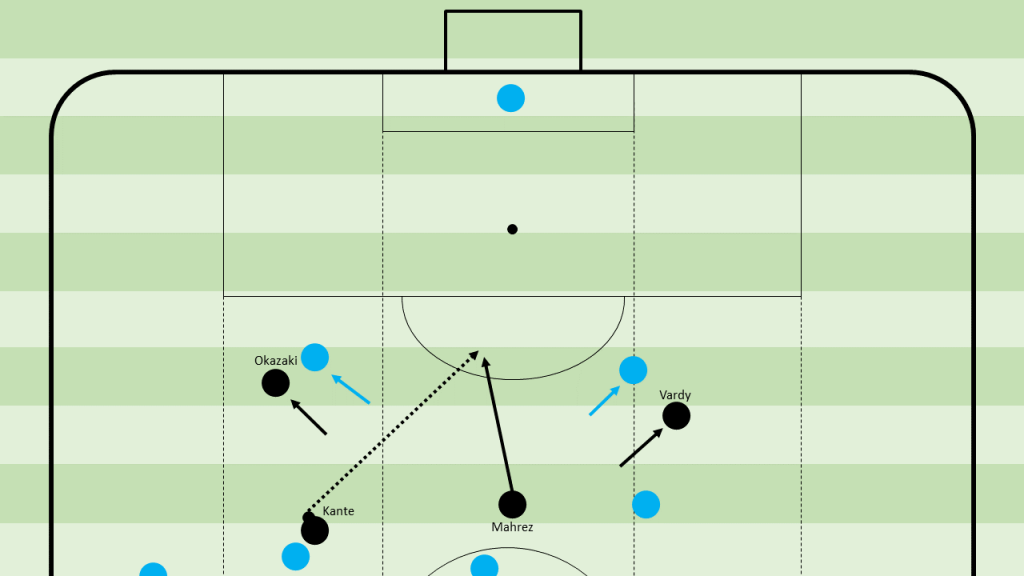

Rather than looking in behind for the strikers, they could also be used as the first outlets as a lay off option to get out of the immediate pressure and access another player with a forward-facing view (who can then play in behind). Especially Okazaki was normally positioned deeper than Vardy to defend but also to be a direct outlet for counterattacks after winning the ball. Even some quick passing combinations such as one-two’s between the strikers were executed from time to time.

However, the strikers obviously couldn’t do it alone. The wingers – Mahrez with his speed in particular – regularly supported the forwards with runs in behind. Additionally, even the fullbacks could over- and underlap at times, starting from a deeper position. This enabled them to reach a higher speed and break through with a dynamical advantage.

Direct approach in possession

Similar to their counterattacks, Leicester City was extremely direct in “settled” possession as well. The Foxes welcomed chaos with their long balls and looked to generate a game of transitions. They constantly found themselves in situations where neither team really had control of the ball. Leicester only attempted 282 short passes per game (18th in the league) on average and played the fifth most long balls per game in the Premier League (72).

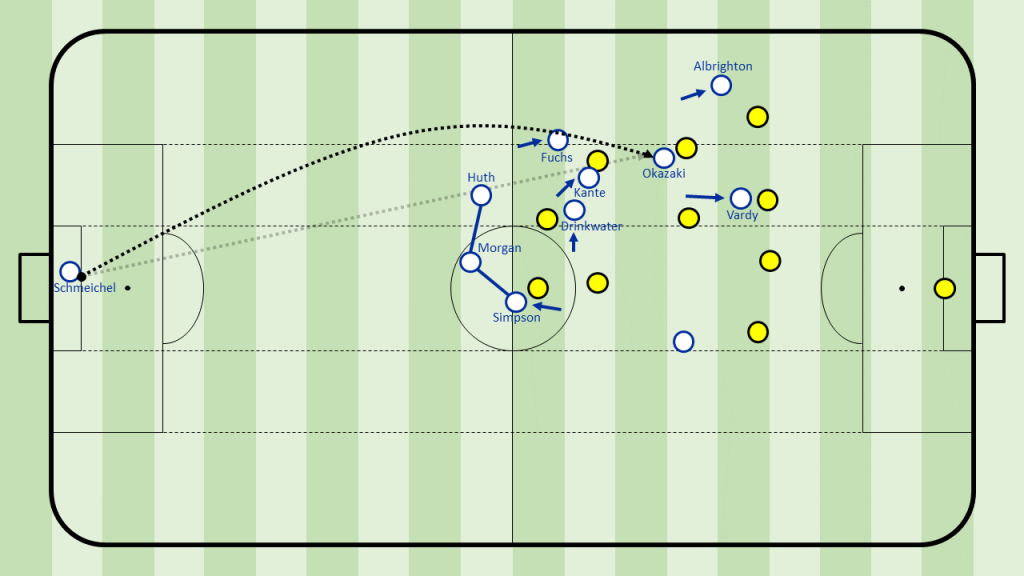

Going long from the goal kick

Rather than building up short, Schmeichel almost always went long from the goal kick. The Dane attempted the highest number of long balls of goalkeepers in the league (1146 long balls) and the least number of short passes (76) compared to other goalkeepers in the Premier League with a minimum of 25 games.

Huth and Morgan weren’t the most technically gifted players and therefore going long was somewhat of an understandable approach. Additionally, by going long the ball was far away from their own goal and they could quickly counterpress second balls (basically generating artificial transition-like scenarios).

The goal kicks were mostly aimed at a striker into a half-space, who was usually well supported to ensure lay off options and access for second balls. While one striker challenged for the ball, his partner was usually positioned higher up the field alongside the ball-near winger to provide options in behind or challenge there if the ball was overhit. The double pivot usually shifted across, supporting the striker with lay off options in front of him. The ball-sided 6 was mostly positioned slightly higher, while the far-sided one stayed deeper to cover. Moreover, the near-sided fullback was normally slightly higher than his ball-far counterpart, who created a temporary back three to ensure enough safety for potential counterattacks from the opposition.

Leicester could either win the ball from the goal kick and transition forward or if the opponent won the initial header and/or second ball, the Foxes would counterpress relentlessly to win the ball back again (to then counterattack themselves again). Leicester’s double pivot – especially Kante – won a lot of second and third balls for the Foxes after a long goal kick. Their ability to read the ball and apply the right amount of pressure was incredibly vital for Leicester.

However, controlling the ball from these types of situations is extremely difficult in general, as Evert van Zoelen describes in his article on long balls:

“Long balls can be excellent situations to apply counterpressing, especially the dead ball and chosen ball situation, as you have control over the structure of your team. In addition, as the ball is difficult to control it’s hard for the opposition to play out underneath the press within the first couple of passes. Especially as they usually lack width themselves as they just moved into a compact shape to defend the long ball.” (Zoelen)

Additionally, since the long balls were mostly aimed into a half-space, Leicester could use the sideline as an extra defender to counterpress or the ball would go out for a throw-in, which the Foxes could press pretty aggressively too.

Leicester kept on counterpressing as long as the ball was bouncing. Moreover, misplaced through balls were a trigger to apply pressure too, since the opposition usually has a negative body orientation (towards their own goal). However, as soon as the opposition was able to find a free player with lots of space, who could control the ball, Leicester would drop back into their 4-4-2 defensive shape and try to defend their goal.

The Algerian dribble and playmaking king

Riyad Mahrez was just a joy to watch in the 2015/16 season. Leicester regularly looked to isolate him on the right-hand side, where he would humiliate defenders in 1v1s. Moreover, he could attract various opponents (and even outplay them), which opened spaces somewhere else for his teammates. This was key both in settled possession and during counterattacks. Additionally, the Algerian created chances out of literally nothing by cutting inside with his left foot. His through balls and in-swinging crosses especially were very threatening.

Mahrez scored 17 goals, provided 11 assists and played 68 key passes (8th highest in the league) with 11 of them being through balls (3rd most in the Premier League). Furthermore, he attempted the second most dribbles per game in the Premier League (3,5).

Final thoughts

In the end, Leicester didn’t do anything earth-shattering from a tactical point of view, but got the basics right, capitalised on their opponents’ weaknesses – which were in fact many during that time – and had a bit of luck too. A last statistic, which underlines the effectiveness of their approach is that they scored the third most goals (68) out of only the seventh highest number of shots (522) in the Premier League.

Claudio Ranieri showcased what’s possible in football and the Foxes arguably wrote one of the greatest underdog stories in sports history.

If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact us.